Temporomandibular joint (TMJ) anatomy and function

Below is a narrated animation about TMJ anatomy, disc displacement and natural adaptation. Click here to license this video and/or other related videos on Alila Medical Media website.

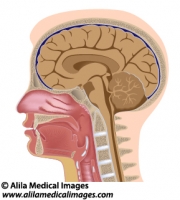

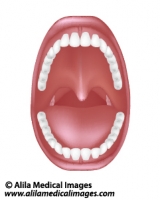

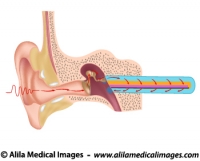

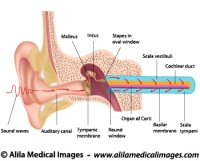

The temporomandibular joint (TMJ) is the joint between the lower jawbone – the mandible – and the temporal bone of the skull (Fig. 1). The TMJ is responsible for jaw movement and is the most used joint in the body.

The TMJ is essentially the articulation between the condyle of the mandible and the mandibular fossa – a socket in the temporal bone. The unique feature of the TMJ is the articular disc – a flexible and elastic cartilage that divides the joint into two parts: a upper joint and a lower joint.

.

.

Fig. 1 : Anatomy of the TMJ with jaw closed and open. Click on image to see a larger version on Alila Medical Media website where the image is also available for licensing.

The disc serves as a cushion between the two bone surfaces. The disc lacks nerve endings and blood vessels in its center and therefore is insensitive to pain. Anteriorly it attaches to lateral pterygoid muscle – a muscle of mastication (chewing). Posteriorly it continues as retrodiscal tissue fully supplied with blood vessels and nerves. This is commonly the source of pain in disorders with anterior disc displacement (see below).

The jawbone (mandible) is the only bone that moves when the mouth opens. The first 20 mm (three quarters of an inch) opening involves only a rotational movement of the condyle within the socket. For the mouth to open wider, the condyle and the disc have to move out of the socket, forward and down the articular eminence, a convex bone surface located anteriorly to the socket (see Fig.1 and video below). This movement is called translation.

Click here to see an animation of normal TMJ function on Alila Medical Media website where the video is also available for licensing.

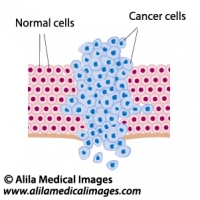

TMJ disorders

The most common disorder of the TMJ is disc displacement, and in most of the cases, the disc is dislocated anteriorly (Fig. 2, middle and lower panels). As the disc moves forwards, the retrodiscal tissue is pulled in between the two bones. This can be very painful as this tissue is fully vascular and innervated, unlike the disc. The movements made by chewing or even talking cause a chronic bruise to the tissue resulting in inflammation and pain.

Fig. 2 : Anterior disc displacement, “clicking” and “locking” symptoms, see text for details. Click on image to see a larger version on Alila Medical Media website where the image is also available for licensing.

The forward dislocated disc is an obstacle for the condyle movement when the mouth is opening. In order to fully open the jaw, the condyle has to jump over the back end of the disc and onto its center. This produces a clicking or popping sound. Upon closing, the condyle slides back out of the disc hence another “click” or “pop”. This condition is called disc displacement with reduction. In later stage of disc dislocation, the condyle stays behind the disc all the time, unable to get back onto the disc. The clicking sound disappeared but mouth opening is limited. This is usually the most symptomatic stage – the jaw is said to be “locked” as it is unable to open wide. At this stage the condition is called disc displacement without reduction.

Click here to see an animation of TMJ disc displacement on Alila Medical Media website where the video is also available for licensing.

Fortunately, in most of the cases, the condition resolves by itself after some time. This is thanks to a process called natural adaptation of the retrodiscal tissue, which after a while becomes scar tissue and can functionally replace the disc. In fact, it becomes so similar to the disc that it is called a pseudodisc.